Madam Dramaturgy

Madam Eliza Haycraft

February 14th, 1820-December 5th, 1871

Not much is known about the early life of Eliza Haycraft for certain beyond that she arrived in St. Louis in 1840 at age 20 from Calloway County, Missouri, possibly by canoe, possibly cast out by her family after an affair. Eliza arrived penniless and with few options to support herself, she turned to sex work. Possessing “unusual personal attractions and a warm and confiding nature” according to the St. Louis Daily Democrat, Eliza rose quickly in her career. She took advantage of the city’s growing population, which largely included young men coming to seek out a life in the big city, and grew her business along with it. She owned two brothels by the start of the Civil war and five by its end, particularly boosted by the Union choosing to decriminalize prostitution during the war.

The Madam also owned other commercial and residential properties which she rented out, some to fellow Madams. Eliza became known for her philanthropy. She never turned away beggars on her doorstep and she donated thousands of dollars in today’s money to the poor. The Madam was able to become an incredibly wealthy and notable figure while also remaining illiterate her entire life, signing documents simply with an “X”.

Eliza retired in 1870 and moved into a home purchased from the prominent Chouteau family where she died on December 5th, 1871 at age 51. Newspapers reported over 5,000 people attended her funeral, both black and white, and rich and poor. Eliza was buried at Bellefountaine Cemetery, the same resting place as many of her high profile clients. The cemetery were at first resistant to selling her the plot, due to her career, but eventually caved to pressure, on the grounds that she would have no headstone. Eliza still rests there over 150 years later, in an unmarked plot, surrounded by 20 empty plots where her girls never came to join her.

"Billie" is inspired by:

Cathay Williams

Cathay Williams (1844-1893), or William Cathay as she was known during her time in the Union Army, was the first woman to enlist in the United States Army. While over 400 women posed as male soldiers to fight in the Civil War, Cathay is the first African American woman, as well as the only documented woman to fight as a man during the Indian Wars, along with being the only known female Buffalo Soldier.

Cathay was born in Independence, Missouri in 1844 to an enslaved mother and free father. Inheriting the status of her mother, Cathay grew up working as a house slave on the Johnson Plantation outside of Jefferson City, MO. In 1861 when the Union occupied Jefferson City, captured slaves were considered contraband and often served in military support roles. Cathay served as a cook and a laundress before deciding to enlist under her false name on November 15th,1866.

“William” enlisted for a three year engagement and was able to pass herself off as a man after a not so thorough medical examination. Shortly into her time serving she contracted smallpox and was hospitalized. She was able to rejoin her unit in New Mexico, but the combination of heat, disease and years of marching put a strain on her body and she was frequently hospitalized, where a surgeon finally discovered she was a woman and informed the post commander. She was honorably discharged October 14,1868. Her time in the general army was over, but she went on to sign up for an emerging all-black regiment that would go on to become part of the Buffalo Soldiers.

After her time in the army Cathay became a cook at Fort Union, New Mexico before moving to Colorado. She married briefly, but it ended poorly after he stole her money and a team of horses and she had him arrested. She moved from Pueblo, CO to Trinidad, CO and began work as a seamstress. Around this time news of her story began to become public and a St. Louis' reporter became interested and came to interview her. The story was published in The St. Louis Daily Times in January of 1876. Near the end of her life Cathay entered a hospital and applied for disability pension. She was rejected, despite there being a precedent for awarding pension to female soldiers. Her exact death date is unknown but thought to be sometime in 1893 after the denial. Her final resting place is unknown.

"Tennie" is inspired by:

Tennessee “Tennie” Clafin

Tennessee “Tennie C.” Claflin (1844-1923), along with her sister, Victoria Woodhull, were the first women to open a Wall Street Brokerage Firm in 1870. Tennie was born in Ohio to an abusive snake-oil salesman father and religious fanatic mother. The girls were involved in their father’s schemes from childhood, being passed off as mediums and healers at tent revivals. In 1853 Victoria married and moved away, but Tennie and her father continued her healing tour. In 1863 her father rented out a hotel in Ottawa, Ill and advertised Tennie’s ability to cure cancer. In reality they were burning people with lye and in 1864 the hotel was raided by authorities and Tennie faced the most serious charge, as she was blamed for the death of at least one patient, but the family managed to avoid ever going to court.

In 1868 the family met Cornelius Vanderbilt, a business magnate who was interested in Tennie’s magnet healing. Tennie and Cornelius began spending time together and are rumoured to have had an affair though he was 50 years older than her and even asked her to marry him, though she declined. However this connection was important later when in early 1870 they launched their brokerage firm, Woodhull, Claflin & Company with the financial backing of Cornelius Vanderbilt. The “Bewitching Brokers” were initially looked at as a curiosity and the sisters were questioned for their association with spiritualism, but they found their audience with the women of high society New York and the firm became successful. The sisters used the profits to start a “radical” newspaper, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, where they spoke on spiritualism, free love, women’s suffrage and socialism.

In the 1870’s the sisters became more involved in political work, attempting but ultimately failing to vote in an 1871 municipal election. Tennie attempted to run for New York’s 8th congressional district in 1871 as well, even giving her candidacy speech in German to the mostly German-American district. Her sister Victoria was nominated to run for president by the newly formed Equal Rights Party in 1872, but her campaign was largely ignored by her nominated running mate, Frederick Douglass, and overshadowed by scandal when the sisters’ newspaper published accusations of an affair by prominent preacher Henry Ward Beecher.

After the Beecher scandal the sisters spent months in and out of jail for publishing “obscenity” and the two left the country for London soon after the trial in 1877. In 1885 Tennie married Francis Cook, Viscount of Monserrate and shortly after their marriage Queen Victoria created a Cook Baronetcy, making her both Viscountess and Lady Cook. She ran a bank for a short time in 1901 after her husband's death, but largely spent the rest of her life outside of the public eye, though she never abandoned her feminist beliefs. She died in London January 18th 1923.

"Ripley" is inspired by:

Martha Ripley

Martha Ripley (1843-1912) was born in Lowell, Vermont on November 11th 1843. Her family moved to the Iowa frontier in her youth where she attended school, though she did not get a diploma. She married William Warren Ripley, a rancher from a Massachusetts mill family in 1867 and the couple moved to Middleton, in his home state shortly after and had three daughters. Her husband first worked for his uncle’s Mill before opening his own, and it was in the mills that Martha’s interest in medicine took hold. Seeing the epidemic of health issues sweeping the women who worked in the textile mills, Martha enrolled in Boston University’s medical school in 1880. In 1883, her husband was involved in a mill accident and forced to retire, the same year she graduated with her M.D. Her career was now pivotal to the family’s financial survival.

The Ripley’s relocated to Minneapolis, Minnesota, where William had relatives and after some initial struggle Martha was one of the first two dozen women in the state to become a licensed doctor, establishing her practice and becoming a successful obstetrician in 1883. The same year she was elected president of the Minnesota Women’s Suffrage Association, a position earned from her connections from her time serving on various committees with the Massachusetts Women’s Suffrage Association from 1875-1883.

Martha was outspoken on public health issues during her time as president of the association. She spoke on clean water and food, hospital crowding and sanitation, and advocated for women to participate more in the city board and policing. Martha was also a passionate advocate for young girls, working to raise the age of consent, (only 10 in MN at the time) and to provide healthcare for women and children who had trouble accessing it in hospitals, which would turn away unmarried pregnant women. She established her Maternity Hospital in 1887 to provide for women in these circumstances. The hospital grew and moved locations in 1896 where it became the hospital with the lowest maternal mortality rate in the area and was the first to establish a social services department. This hospital, later renamed the Ripley Memorial Hospital, operated until 1957.

Martha died on April 18, 1912 from a respiratory infection and heart disease. She was cremated, but is honored by a plaque in the Minnesota state capitol building, remembering her as a hospital founder and foundational woman physician in the state. She is also remembered through the Ripley Memorial Foundation, founded with the proceeds from the sale of the old hospital structure which supports programs to prevent teen pregnancies.

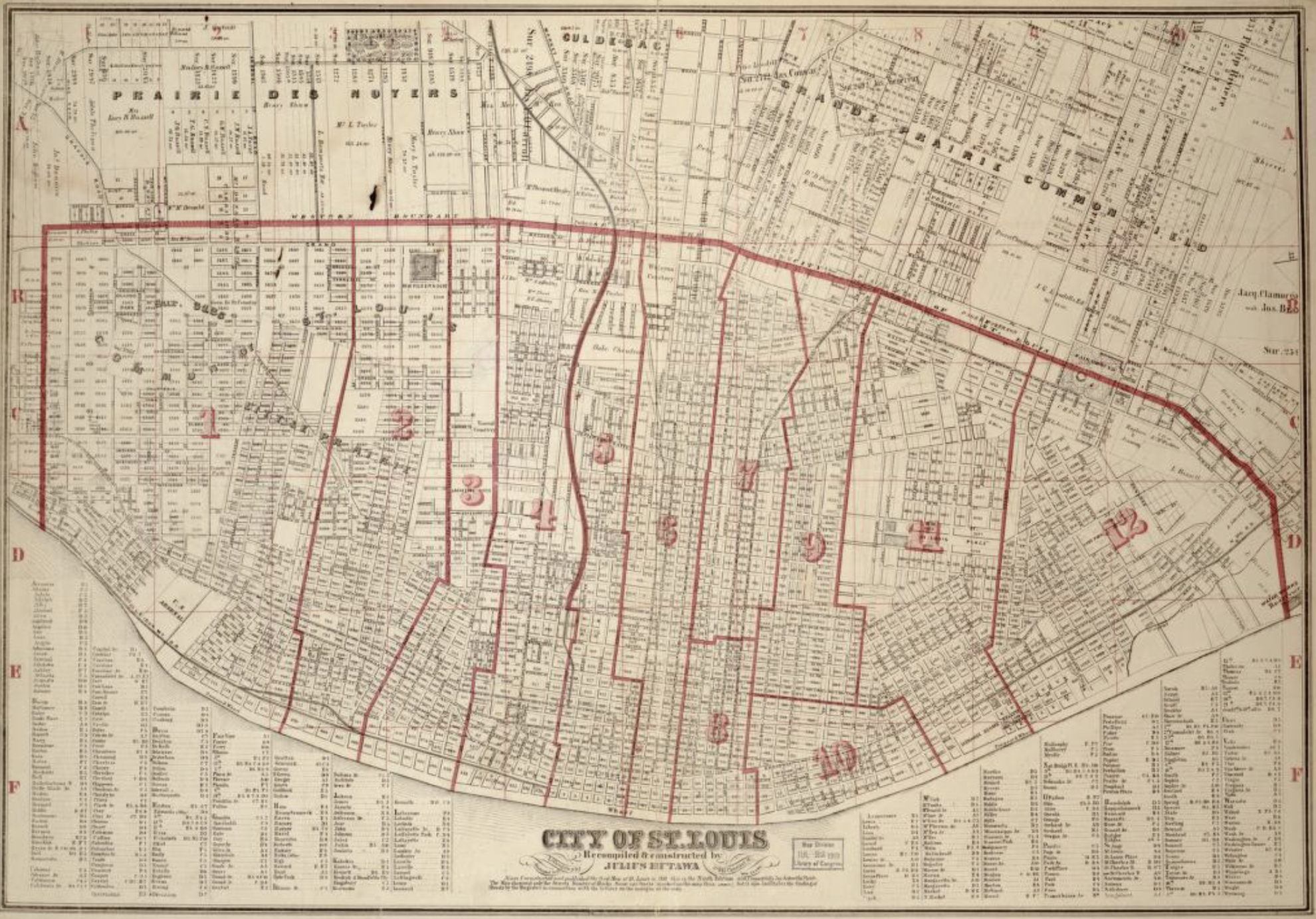

St. Louis in the time of Madam

19th Century St. Louis was a place of constant change and development. The city had gone from Spanish territory, to French, to part of an official U.S. state in just the first two decades. The city survived tornados, cholera epidemics, and great fires, which led to changes in building code that made St. Louis the brick city it is today. From 1840-1870 the city’s population increased tenfold. The first half of the century brought an increase in Irish immigrants fleeing famine, and German immigrants, who brought abolitionist beliefs with them. The arrival of the civil war left the St. Louis divided, the largest city in a border state, it held importance for both sides due to its proximity to the river, an important route for transportation of both soldiers and supplies. Missouri never succeeded and the city remained under Union control during the war, but sympathies inside the city remained on both sides.

By 1870 Missouri was the 5th most populated state at the time and St. Louis was the 4th largest city in America, with a population of 310,864 according to the 1870 census. The city continued to see European immigration, as well as an influx of black war refugees from the south, and those passing through on the journey west. The city began working to improve infrastructure that had been ignored during war time. Water systems were improved,railways and public transportation were expanded, including the first bridge over the Mississippi River in 1874. Parks systems and libraries were put in place and effort was made to establish better quality schools for black students, though the deep inequality remained. The expansion of the railroad allowed for easier transport for St. Louis’s booming beer and brick industries. However the city’s growth was not all for the better. The 1870’s was a time of whiskey based fraud conspiracies and labor abuses leading to one of the United States’s first general strikes. In response to the unrest and strikes militias were formed and the police were given more power to suppress them.

The Social Evil Ordinance

As the city’s post war population grew, so did its sex worker population, leading St. Louis to become the first city in the United States to legalize prostitution. The Social Evil Ordinance was overwhelmingly approved in July of 1870 in an attempt to control the spread of venereal disease and “immorality” in the city. The ordinance required prostitutes and brothels to register with the city police, undergo regular medical exams, and to pay a fee to the city board of health. The law was revised in 1871 to establish the Social Evil Hospital, after female patients at the city hospital complained about sharing a ward with “fallen women”. The new separate hospital opened in the fall of 1872 at the corner of Arsenal and Sublette Avenue, along with a house of industry where the women could be trained in more socially acceptable skills.

The experimental act didn’t go exactly as planned. The house of industry was closed almost immediately as the woman had no desire to be reformed. Many of the women simply did not comply with the law and ignored the rules.Critics of the ordinance felt it gave the police too much power, and the physical exams meant to control the spread of disease often did not happen as promised. Other times women were compelled to receive treatment they didn’t want. The law was created under the guise of protecting women, but largely blamed them for the industry’s problems and removed the power they once had over their own businesses. The ordinance was nullified in 1874 after greatly decreasing popularity with the public. The Social Evil Hospital was renamed The Female Hospital and remained in operation as a general women’s hospital until 1910.